By Lucy Komisar

Dec 31, 2008

Arthur Miller’s play about corporate corruption never goes out of fashion. As a theater device, he focused on a small factory owned by one man, but you can take this as a representation of what went on and what goes on when anything goes in business. Profits trump morals. The victims are all of us, which is what the title means. Simon McBurney’s production is smooth and riveting, with a cast that acts with the fluidity of an ensemble.

All My Sons, first produced in 1947, is a psychological drama enveloped in mystery that unfolds to shock. Kate Keller (Dianne Wiest) has not taken the wartime death of her son Larry easily. His plane was reported missing, his body was not found. She keeps his room ready and refuses to believe he won’t come back. Her husband Joe (John Lithgow) won’t contradict her.

When Larry’s girlfriend Ann Deever (Katie Holmes) comes to visit, she brings with her more than the memory of the flyer. She evokes the story of the terrible event that sent her father to jail. The factory Steve Deever and his partner Joe Keller ran had sold 120 cracked engine cylinder heads to the Army Air Force. Twenty one P-40’s that had the  parts crashed in Australia, killing the flyers.

parts crashed in Australia, killing the flyers.

The neighbors called the partners murderers. But Joe got out of jail by accusing his partner. He said he was home with the flu and that Steve made the decision to ship the cylinders.

Miller laces the story with subtle provocative clues. Kate tells Joe to stop joking with neighborhood kids about jail. What have I got to hide? he asks? Lithgow’s fine portrayal of Joe is all bottled energy, even a bit of a bully.

Ann had stopped visiting her father after Larry was killed, thinking maybe he was in a plane that got the faulty part. Kate tells her never to say that again. And Joe insists that, Those cylinder heads went into P-40’s only. What’s the matter with you? You know Larry never flew a P-40. Why should that matter?

Steve’s son George, now a lawyer, is arriving after a visit at the jail. Kate is nervous. Why, Joe? What has Steve suddenly got to tell him that he takes an airplane to see him? Diane Wiest moves between a vague haziness and lucidity.

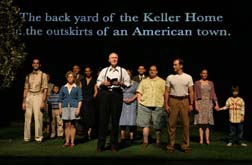

There’s a stylized 40s feel to the play. It’s a drama that is not melodrama; it’s even faintly poetic. The actions are set in a mood of the very prosaic, with neighbors passing through the backyard and talking about children and cooking and horoscopes. When not on stage, they sit on chairs on either side, dark shadows representing the people of the town, representing society watching what transpires.

The neighbors don’t believe Joe. Sue says, Who is he to ruin a man’s  life? Everybody knows Joe pulled a fast one to get out of jail.

life? Everybody knows Joe pulled a fast one to get out of jail.

George (Christian Camargo), who hadn’t believed his father before, has now changed his mind. He believes the story that Steve Deever had called Joe to say there were defects in the cylinder heads. What should he do? And Joe told him to weld them to cover up the cracks and ship them out.

Projections on the backdrop show Larry flying towards us. The larger truth of the event, and of Kate’s refusal to accept Larry’s death, is hinted at by his brother Chris (Patrick Wilson) who speaks for Miller in his hope for the post-war world. Chris says that there would be a kind of…responsibility. Man for man. But he came home and saw that nobody was changed at all. He said that people who enjoyed material things, cars new refrigerator, had to appreciate people who fought for them. Otherwise what you have is really loot, and there’s blood on it.

NY Theatre-Wire