By Lucy Komisar

It creeps up on you, this fascinating play that highlights a gripping Kathleen Chalfant, which at first seems like something from the years‘ ago “ban the bomb” movement. And then you realize that it is an up-to-the-minute chilling warning of a threat hanging over our heads. And you wonder why it disappeared from the media.

Lee Blessing‘s “A Walk in the Woods” was first performed in 1988 when the Cold War was raging. A year later, when the Berlin Wall fell, that was supposed to be over. But, guess what, it turns out the massive buildup of arms had nothing to do with real enemies. The reason for it is one thing that Blessing‘s play doesn‘t address: on the American side, Eisenhower called it the military industrial complex. Generals who promote their status and corporations who pull in profits. And one hand washes the other. So when you see what is said in this play, you have to ask why.

The script was inspired by the meeting between Paul Nitze and Yuli Kvitsinsky, who took a ”walk in the woods” during the 1982 Geneva peace talks and came up with a deal which was turned down by the United States and the Soviet Union.

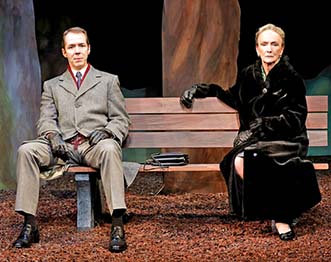

This two-hander, Irina Botvinnik, a Russian arms negotiator played by Chalfant, and John Honeyman, her American counterpart portrayed by Paul Niebanck, makes very clear that for the system, the two sides, it was all a fraud. The negotiators were sent to talk to delay, to prevent any arms reduction plan from being approved.

Chalfant is superb, with a perfect Russian accent, which she used in a talk-back session. Niebanck is the prototypical bureaucrat, so maybe he plays him flat on purpose. The production is coolly directed by Jonathan Silverstein. The play was written for two male actors, but using a tough but sensitive woman brings more humanity and personal conflict to it.

Irina says, “We make proposals and they nearly always fail.” But, as she notes, looking at the years when some treaties were signed, they were immediately followed by arms races on whatever items weren‘t included. They would be bargaining chips for the next treaty. It was all a fraud!! And still is. She suggests that rather than have negotiators sit in peaceful, rich Geneva, they should remove the tables to the bottom of a missile silo.

But the play doesn‘t entrap you in MEGO (remember my eyes glaze over) stuff about the technicalities of arms reduction. Partly, of course because they were also frauds. Excuses.

Paul Niebanck as John and Kathleen Chalfant as Irina, photo Carol Rosegg.

The two negotiators meet in the woods of Geneva where, of course, international diplomacy takes place – so peaceful, so beautiful. Irina tries to get to her counterpart‘s human side. She wants to be friends. He is standoffish. Of course, she knows that the whole enterprise is a charade, and they might as well enjoy the Geneva summer, then the fall, the winter and the spring. We know that by the change of their clothing. And leaves falling from the trees of Scott Bradley‘s set.

Irina‘s focus on what she calls “frivolous” stuff seems bizarre. The serious American takes it that way. But along the way a proposal his government makes has a chance of being accepted by the Russians, except the US president needs to announce it for political reasons before an election, so the Russians of course then reject it.

Not, Irina says, that the Russians don‘t have their own political constraints. She says, “We have hawks, and sometimes the hawks eat a few doves.”

I liked Blessing‘s description of a US that because of geography conquered without competition (threats on borders) and a Soviet Union that conquered because of that competition. And both created empires. The Americans decided that they were idealists, and the Russians felt themselves realists. Irina says they both share delusions that they are peace-loving. But if they gave up desire for dominance, the U.S. would be Canada and Russia an enormous Poland.

And if both sides really wanted disarmament, there would be millions of “us” – the negotiators – and only two soldiers. But Irina says, “You and I are made for playing games in the woods.”

Chalfant is almost too real as the cynical but in many ways generous diplomat in her 60s, dealing directly but candidly with an American who is much younger, maybe 40, who has come up from the bureaucratic ranks and doesn‘t yet know how the system works.

“A Walk in the Woods.” Written by Lee Blessing, directed by Jonathan Silverstein. Keen Company at Clurman Theatre, 410 West 42nd Street, New York City. 212-239-6200. Opened Sept. 17, 2014; closes Oct. 18, 2014. 10/3/14.

Thank you. Alva Myrdal (“The Game of Disarmament” , 1976) and E.P.Thompson (“Notes on Exterminism, the Last Stage of Civilization” , 1980) come to my mind. I wish I were in New York so that I could visit the Clurman Theatre to see this play. But I am in Finland and will have to put up with a videoversion, if such is coming.