By Lucy Komisar

Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil found worldwide success with Les Misérables, a drama of the political. The personal stories were of Jean Valjean, the man imprisoned for stealing a loaf of bread, and the masses of the oppressed he represented. There was a minor love story. But in Miss Saigon, the star-crossed lovers are the major focus, with the crisis of America‘s war in Vietnam and how it destroyed the country just a backdrop. So, this play is often hokey and not very satisfying.

The best parts are terrific production numbers about real events, especially the thrilling dragon dance of the Vietcong that shows its victory over the U.S. And the famous desperate scramble of people trying to get into the U.S. embassy grounds to catch the last helicopter out. There are loud sounds of the chopper. Choreography is by Bob Avian.

They could have been an exciting focus. Instead, we see what eventually becomes the tedious story of the desperate prostitute dancers (upsetting but not made real), and the clean GI, Chris (Alistair Brammer), a driver for the embassy, who falls for a “virginal” new recruit, Kim (Eva Noblezada), whose village and family have just been wiped out by the Americans. The plots becomes their love affair and his unsuccessful attempt to get her onto the helicopter.

Her betrothed, Thuy (a very fine Devin Ilaw), to whom she was promised without her consent at 13, becomes a Vietcong army officer. He is shown as the bad guy. I’d have liked more about him.

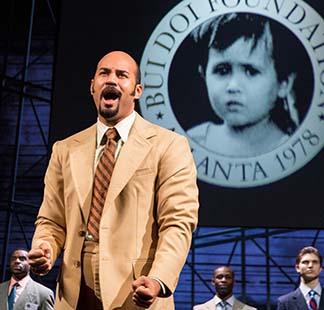

We get a good picture of Jon Jon Briones, excellent as the sleazy Luoyong Wang, “The Engineer,” whose nickname comes from the fact he engineers a lot of the lowlife dealing at the Saigon disco bar.

His best line is after the fall of that city when he dreams his fantasy of America, where he can cash in on his pimping. In a glitzy convertible, with a nude woman in white mink, he drives out of the mouth of the Statue of Liberty. “America is great” he declares. It gets a big laugh.

This show could have been an important political moment. But, unfortunately, when politics meets soap opera, soap opera wins. The show now seems sentimental, dated.

The cast is talented. Chris has a near operatic voice, Kim‘s soprano is fine. The dancers, especially in the martial Vietcong number, are superb.

The set design by Totie Driver and Matt Kinley and projections by Luke Halls are high-concept Broadway. Much of the set is garish and tacky. You think you are there with the red flares of bombs going off in 1975 when the Americans were defeated.

The video montage of children left behind by American fathers is a bit too much like something you would see in a fund-raising telethon. A bit exploitative. Collateral damage.

Though Kim sings of looking for a man who will not kill, only one line gets to the point where Chris says something about the wrong war. “This is the end of the line, this whole rotten scene…It‘s time to go home, it‘s time to get clean.”

And at the closed gates that bar them from the escape helicopter, you see the “loyalty” the Americans paid to those who had helped them:

Vietnamese: Take me with you –

Vietnamese: Take my children –

A Vietnamese: I have a letter here –

A Vietnamese: I helped the C.I.A.!

Vietnamese: They‘ll kill who they find here!

don‘t leave us behind here!

But of course they did. Reminds one of immigration authorities turning back people who had worked for the Americans in Iraq.

The play was inspired by a photo in France Soir magazine that showed a Vietnamese girl saying goodbye to her mother to board a plane from Ho Chi Minh City for the United States to live with her father, an ex-G.I. she had never seen. So, the last desperate act is the one Kim does to “save” her child. More collateral damage.

The problem with references to collateral damage is that, as in this case, they often finesse what caused it.

“Miss Saigon.” Music by Claude-Michel Schönberg, lyrics by Richard Maltby, Jr. & Alain Boubil, adapted from French original text by Alain Boubil, directed by Laurence Connor, musical staging & choreography by Bob Avian. Broadway Theatre, 1681 Broadway, New York City. 212-239-6200. Opened March 23, 2017. 6/13/17.