By Lucy Komisar

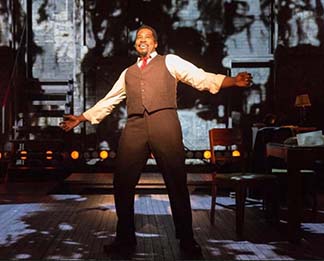

Daniel Beaty‘s portrait of Paul Robeson in his one-man show at the Brooklyn Academy of Music is stunning and moving. Memorable. It won an immediate standing ovation. Of course, Beaty had as a subject a man of great talent, courage and fortitude. For Americans to understand their history, this play should be seen in universities and theaters around the country.

Beaty, in a performance powerfully directed by Moisés Kaufman, makes you shiver at the cruelty of the U.S. government persecuting Robeson for daring to express his views, and then cheer at the man‘s grit, with just a few reservations. And because in mainstream histories, he‘s not given his due, it‘s worth talking about the details as Beaty dramatizes them.

Robeson was born in 1898. His father, who started life as a slave, became a minister and in New Jersey taught his son The Odyssey in the original Greek.

Robeson also heard a lesson about survival. When his brother fought a white antagonist, his father warned him, “To stay alive, don‘t make white people angry.” (He forgot that in later years.) No Uncle Tom, his father, a minister, pushed him to greatness. The third Negro admitted to Rutgers University, he graduated valedictorian.

In John Narun‘s fine projections, we see Harlem, where “The Joint is Jumpin,” and Robeson gives concerts to raise his tuition to Columbia Law School. Beaty‘s voice reverberates with the gospel “Get on Board.” It‘s not quite Robeson quality, but it‘s very good. He meets Islanda, who will be his wife. She advises him to rise up and ditch the slave songs. (Beaty plays all the characters and does a good job at it, even if Islanda’s voice is a little hokey.)

Then, working for the Stokesberry law firm, a secretary calls him nigger. And he tells his boss, “I am tired of preparing brilliant briefs for white lawyers to try.”

The boss says, “Courts wouldn‘t accept cases from a black man” and proposes he open a branch in Harlem. Robeson resigns.

He gets a role in Eugene O‘Neill‘s “All God‘s Chillun Got Wings,” about interracial lovers. He has an operatic voice and his wife, known as Essie, is a crafty manager. He does a masterful “Porgy and Bess.”

In London, they become the toast of English aristocracy. But one night they are denied entrance to a restaurant they have frequented, because the ma®tre d‘ says that the Americans there don‘t want to dine with Negroes.

Back home, he is attacked by The Amsterdam News for singing about “niggers.”

Beaty doesn’t stint on Robeson’s faults. On a personal level, he is not the model husband. In London, 1930, he has an affair with actress Peggy Ashcroft, Desdemona to his Othello. His wife remonstrates, “You‘re not in love, you‘re a Negro musician chasing white meat. (Later, on Broadway, he‘ll get involved with Uta Hagen, also playing Desdemona.)

But the life-changing event in England is seeing Welsh miners marching to protest unemployment and hunger. We see them in dramatic videos.

He buys lunch for 200 miners and joins their march to Parliament, where police close in on them. He sings, “Let my people go.”

Robeson, wanting to use his talent to promote his politics, is deceived by a film maker into doing a movie about an African tribal leader, “Sanders of the River,” which the director edits to make it advocate for the British. An African asks him to use his celebrity to support them, and he speaks out against British terrorizing of Africans.

As his political consciousness rises, Robeson sets off on a trip to the Soviet Union. It‘s 1934, and he stops in Berlin. Nazi storm troopers encircle him and Essie. “Schwartze, was tun du mit dieser weisser Frau.” (Using the insulting intimate du for you instead of the polite Sie.) “Black, what are you doing with this white woman.” Essie was light-skinned.

He arrives in Moscow and is welcomed by world-famous director Sergei Eisenstein. He sees blacks, Chinese, Jews working together. And nobody sits in the back of the bus.

By 1942, it‘s wartime, and he sings “The Ballad for Americans,” which asks people to fight and to buy war bonds against fascism. So, he‘s now a patriot, even does Roosevelt’s Happy Days Are Here Again.

But then black soldiers returning from the war are terrorized, 41 lynched, some in uniform. Robeson leads an American crusade to end lynching.

He meets with Truman at the White House, telling him how many Negroes went to war and returned to be lynched. Truman says now is not the time to pass a law. Robeson tells him that would not happen in Russia.

In 1944, at a celebration of his 46th birthday by 12,000 people at the New York Armory, Mary McLeod Bethune, President of the National Council of Negro Women, calls him “the tallest tree in our forest.”

In 1946-7, Robeson travels across the country speaking against lynching. J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI is on his track, but not on the track of white terrorists. Robeson turns from performer to activist.

Then, in Moscow in 1949, he sees anti-Semitism. He tries to meet Jewish friends and finds it difficult. One friend writes on a pad, “The room is bugged, Stalin has killed many prominent Jews, I have been in jail last 7 months. They released me so you wouldn‘t be suspicious.” We see the text on projections.

He broadcasts a song in Yiddish dedicated to the fighters of the Warsaw ghetto. But he doesn‘t denounce the persecution. On his return he is held by the FBI for six hours. When he declines to report rumors that Stalin has had thousands killed, his wife says, “How could you? Our friends are being murdered. Feiffer asked you to speak out. Our closest friends have been Jewish.” Their son married a Greenberg. Robeson‘s fatal flaw will be to refuse to acknowledge Stalin‘s terror.

In case Americans feel any moral superiority, the play recounts the horror in Peekskill, NY, 1949, when a political music festival was attacked by rightists.

Some 25,000 people, mostly blacks and Jews, had arrived in this town 40 miles north of New York City. Beaty/Robeson sings the strong, emotional “Didn‘t My Lord Deliver Daniel.” And as the throngs leave, they are attacked by mobs lining the ways out. Many wield clubs. The police do nothing. Robeson calls it American fascism. It‘s hard to argue with that.

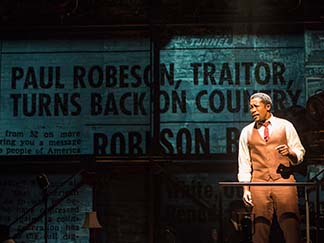

The fitting follow-up is a subpoena by the ironically named House Un-American Activities Committee run by Rep. Francis Walter (D-PA). Robeson is attacked by the committee and derided by the mainstream media as a traitor. The U.S. State Department revokes his passport. Blacklisted in the U.S., he can‘t work at home, and banned from travel, he can‘t earn a living abroad.

He will explain, “If you talk about race, there is a place for you in American history….If you talk about class and race, you get attacked.” He notes that Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated organizing sanitation workers. And he quotes a professor, “When you talk about class struggle, the government will destroy you.” It did its best.

Robeson would die in 1976 at 77, still a lot taller than Hoover, Walter and the others who defamed him.

“The Tallest Tree in the Forest.” Written and performed by Daniel Beaty; directed by Moisés Kaufman. Tectonic Theater Project at BAM Harvey Theater, 651 Fulton St, Bklyn, NY. 718-636-410. March 22 to March 29, 2015. 4/2/15. A Paul Robeson chronology.