By Lucy Komisar

It is Aug 13 2021. Henry Naylor is a topical comedian looking back at the Taliban departure from Afghanistan a decade before. Naylor was a writer for the British TV satire show “The Spitting Image” and a stand-up comic. He likes satires on war like Mash, Catch 22, Dr. Strangelove. A decade earlier, he had a chance to do a show on BBC comedy radio, and he wanted to talk about the Afghanistan conflict, but the state-funded broadcaster said Afghanistan is not funny. Too many dead bodies. He noticed that journalists talking about Afghanistan were not really there. They gathered on the border. Including a BBC reporter who faked reports. Yes, the BBC was full of fakery. Naylor wanted to expose the media lies. So, flashback.

This is a true story. Naylor ends up in Afghanistan in 2002 with Sam Maynard, one of Scotland’s leading photographers. And they get a local fixer, Homayoun, who was a surgeon but made more money working for westerners.

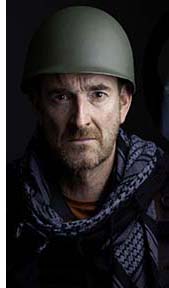

He gives a stunning performance, playing all characters, and with the help of directors Darren Lee Cole and Martha Lott, you believe you are in London and Kabul.

He is dressed in a casual white shirt and slacks and moves effortlessly between two white folding tables and a couple of chairs. But that is enhanced by a backdrop of Sam’s blown-up photos. And– it’s an odd phrase to use – by Naylor’s poetic dialogue.

He says, “There are miles and miles of ruins. It’s like visiting Rome – only these ruins aren’t ancient. These are modern buildings: cinemas. Chemists. Apartment blocks. With the facades ripped off, and the roofs blown away. Skeletons of buildings – with arteries of rusty steel twisting out from shattered walls. And on many buildings you see the three letters UXO with an arrow pointing to the ground.”

What does UXO stand for? “Mr. Henry – it is ‘Unexploded Ordinance.’ It means there is a mine or an unexploded missile or a cluster bomb there, which has not been deactivated.’ We see one building which looks like a crushed ribcage; it looks like it’s going to collapse at any minute..…and yet there, in the shadows, is a flash of blue – plastic sheeting – a washing line – and some cheeky children – – and suddenly I realize that there are people living here.”

They come across an elderly man who is the guardian of the mountainside. Naylor says, “He has made a sculpture out of missiles which he’s found on the mountain; stingers, anti-tank missiles, RPGs. We’re posing for photos in front of it, when Sam says, ‘Are those missiles still live?’ The old man says ‘I dunno…’ …and we take far fewer photos than we were intending and are straight back down the hill.”

They visit ministry of women which is run by a powerhouse lady who during the (first) Taliban rule ran an illegal girls’ school from her basement.

They see the kids at the prosthetic limbs factory. Naylor says, “At the time, 82 kids a week were being admitted, having lost limbs due to landmine injuries; there are so many mines in this country.”

Another landmark is a jumble of girders and fallen masonry. Naylor says, “It was blown to bits by the Americans who claimed it was Bin Laden’s nuclear weapons base. Oops. Sorry. It wasn’t. It was just a marble factory. We’re taking pictures in the ruins, when we see a young man. He had been working at the factory the night of the bombing. His colleague on the nightshift had been killed. He survived. He comes to the factory every day, hoping that it will reopen. It doesn’t look like it is going to open any time soon. ‘Why doesn’t he get a job somewhere else?’ ‘There is no work.’ ‘Are the West going to compensate him?’ [Homayoun laughs. Without amusement.]

Naylor needs accreditation to visit U.S. bases. First they go to the American embassy, park outside, are targeted by a watchtower gunner and screamed at, “Move the f—-g car!” Fast escape. Next attempt, Homayoun parks 300 meters away from Bagram Air Base. A truck picks them up and takes them to a holding area. A colonel curses at them, says, “This is a warzone. If I wanted to – I could drive you out into the middle of the desert, and make you disappear.”

They race away. The only good road in the country is from the base to Kabul, but it is heavily mined. The driver goes 90 mph so, by his logic, if the car hits a mine, it might speed past it before it explodes.

They find out later that the U.S. colonel who threatened them was brought up on war crimes charges for taking people from Abu Graib to the desert and making them disappear.

In the market, they learn, “We hadn’t defeated the Taliban. They just melted into the crowd.” High drama comes when they are looking for a tank graveyard and come face to face with some gun-toting Mujhadheen who point AK-47s at them. “I try the universal language of bribery. I offer them a packet of Marlborough. They take the cigarettes and put them in their pocket. They do not move….They lead us at gunpoint, downhill, towards a plain, concrete block in the valley.”

“And in walks the local warlord. After a while, he says, ‘What are you doing here?’ ‘Um. We’re doing a play for the Edinburgh festival.’ ” OK, so this is funny. It can’t happen.

‘A play??’ “Yes, it is going to be ever so good we’re taking photos in the war zone and we going to blow them up the size of the stage, and the actors are going to act in front of it. I’ve never seen anything like it in the theatre before. It’s going to be brilliant, and interactive. The Edinburgh Evening News, I am sure, will give it five stars.’ “

“He leads us outside. Behind the concrete block, there are seven tanks. He waves his men onto them. And they begin driving the tanks around us in a circle. ‘So you wish to show the liberation of Kabul? It was just like this.’

He says, “Two minutes ago, I really thought this man was going to kill us. Now he is restaging the liberation of Kabul for an Edinburgh festival play. And what is even more remarkable – Sam has started to direct them. He is saying, ‘you’re not looking excited enough. Come on! Imagine you’re liberating Kabul. Punch the air. Shout Allah Akbar!’ And they start punching the air..”

Naylor is very persuasive. The warlord tells him how to find the tank graveyard. It’s scary and funny. So, he has escaped near death threats from the Americans and the Taliban.

There’s a scene of children playing empty food tins like drums. On the side of the tins are the letters ‘USA.’ Naylor says, “I can’t understand it. Why is the lettering in English? None of these people can understand it. And then I realize the food aid is not for the benefit of these people. The fact is, it’s for the cameras, for the Western TV viewers.”

In a repeated anecdote, he tells of coming on a girl carrying a bundle. “The only thing that matters is her story.” When the mystery is solved, it will tell a central truth.

Postscript, when the Taliban took over again, Homayoun, who had worked for westerners, sought U.S. and UK help to get out. Naylor told me after the show, “Those governments were useless. Germany and Canada helped most. It took a year for him to get out to Germany.”

Why did he do the play now, after the Taliban returned? He told me, “When the Taliban came back to power, nobody talked about Afghanistan. There was silence.” He wants to challenge the Western indifference that replaced their killer policies.

A critic’s take from this play: what did the U.S. accomplish in Afghanistan? Mass murder in the service of American global hegemony.

This is not in the show but important: it is Jimmy Carter’s National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinki admitting, even bragging, how he promoted America’s Islamic proxy war in Afghanistan to target the Russians. https://dgibbs.faculty.arizona.edu/brzezinski_interview

Question: The former director of the CIA, Robert Gates, stated in his memoirs that the American intelligence services began to aid the Mujahiddin in Afghanistan six months before the Soviet intervention. Is this period, you were the national securty advisor to President Carter. You therefore played a key role in this affair. Is this correct?

Brzezinski: Yes. According to the official version of history, CIA aid to the Mujahiddin began during 1980, that is to say, after the Soviet army invaded Afghanistan on December 24, 1979. But the reality, closely guarded until now, is completely otherwise: Indeed, it was July 3, 1979 that President Carter signed the first directive for secret aid to the opponents of the pro-Soviet regime in Kabul. And that very day, I wrote a note to the president in which I explained to him that in my opinion this aid was going to induce a Soviet military intervention [emphasis added throughout].

Q: Despite this risk, you were an advocate of this covert action. But perhaps you yourself desired this Soviet entry into the war and looked for a way to provoke it?

B: It wasn’t quite like that. We didn’t push the Russians to intervene, but we knowingly increased the probability that they would.

Q : When the Soviets justified their intervention by asserting that they intended to fight against secret US involvement in Afghanistan , nobody believed them . However, there was an element of truth in this. You don’t regret any of this today?

B: Regret what? That secret operation was an excellent idea. It had the effect of drawing the Russians into the Afghan trap and you want me to regret it? The day that the Soviets officially crossed the border, I wrote to President Carter, essentially: “We now have the opportunity of giving to the USSR its Vietnam war.” Indeed, for almost 10 years, Moscow had to carry on a war that was unsustainable for the regime , a conflict that bought about the demoralization and finally the breakup of the Soviet empire.

Q: And neither do you regret having supported Islamic fundamentalism, which has given arms and advice to future terrorists?

B : What is more important in world history? The Taliban or the collapse of the Soviet empire? Some agitated Moslems or the liberation of Central Europe and the end of the cold war?

Q : “Some agitated Moslems”? But it has been said and repeated: Islamic fundamentalism represents a world menace today…

B: Nonsense! It is said that the West has a global policy in regard to Islam. That is stupid: There isn’t a global Islam. Look at Islam in a rational manner, without demagoguery or emotionalism. It is the leading religion of the world with 1.5 billion followers. But what is t h ere in com m on among fundamentalist Saudi Arabia , moderate Morocco, militarist Pakistan, pro-Western Egypt, or secularist Central Asia? Nothing more than what unites the Christian countries…

Naylor has performed the show in Edinburgh and at festivals in Hollywood, Prague and Adelaide. Not yet in Washington. The killers don’t like to be confronted by the bodies.

“Afghanistan is Not Funny.” Written and performed by Henry Naylor, directed by Darren Lee Cole and Martha Lott. Soho Playhouse, 15 Vandam Street, NYC. Runtime 75min. Opened Dec 1, closes Dec 11. (Dec. 1, 2, 4, 7 and 9 at 7pm; Dec. 3 and 10 at 5pm; and Dec. 11 at 9pm.) Tickets or at the Box Office Tues – Sun after 4pm. Discounts for groups, students, and seniors. Review on NY Theatre-Wire.